Sample Survey for Continuing Education in Dentistry Pdf

Introduction

The Department of Health in England, under Section 63 of the 1968 Health Services and Public Health Act, makes funds available to support the continuing professional education (CPE) of dental practitioners. These 'Section 63' courses are offered free to GDPs working within the NHS, and recently to dentists in the Community Dental Service (CDS). Dentists may attend as many as they like although an away-from-practice allowance can only be claimed by GDPs for two half-day sessions per year. Across the West Midlands region, about half the courses fall within the category of priority areas (formally known as COCET priorities, subjects identified by the Committee on Continuing Education and Training in dentistry, now replaced by NCCPED [The National Centre for Continuing Professional Education of Dentists]), and cover topics defined by these criteria. Recent priority areas for training include courses for GDPs which provide "hands-on" experience, deal with the management of elderly, disabled and special needs patients, give instruction in sedation techniques, pain control and the management of nervous patients. The rest of the courses in the West Midlands are run in response to perceived local needs.

Nationally the provision of continuing professional education for dentists was expanded in 1987 (Department of Health1). Whilst there is evidence of considerable take-up of these opportunities (Mouatt et al.;2 Long et al.;3 Walmsley and Frame4,5,5), a significant number of practising dentists do not attend short courses. For example, in a study of approximately one third of GDPs in Yorkshire (number=307), Mercer et al.6 found that 13% had not attended any courses and that non-attendance was increasing.

In the future, however, non-attendance may cease to be an option. In May 1997, the General Dental Council (GDC)7 issued a consultation document on 'Reaccreditation and Recertification for the Dental Profession'. This proposed 'a system of mandatory continuing dental education' which is based within the GDC's statutory responsibility for the promotion of high standards of dental education at all stages. The Review Group recommended 'an annual commitment to 15 hours of formally approved CPE, ... and a further 35 hours of recorded formal or informal CPE' (p13, para 26). The GDC had already warned as early as 1993 that those who fail to update their skills, and as a result, provide sub-standard treatment 'may be liable to proceedings of misconduct' (GDC).8

Compulsory attendance at Section 63 and other formally approved continuing dental education activity means that quality provision will be of increasing importance. If dentists are required to attend courses they will want to know that procedures are in place to ensure that provision is of high quality and relevant to their needs. An evaluation mechanism which feeds into the planning cycle will be essential for this to be achieved.

This paper reports on a study, conducted between October 1996 and February 1998, examining how short course continuing dental education was monitored and evaluated within the West Midlands region; from this an enhanced evaluation strategy was devised which could be adapted for national use.

Methods

In Phase 1 of the study, interviews were held with the Regional Director and Deputy Director of Postgraduate Dental Education and the eleven local clinical tutors from the eleven local centres in the West Midlands. Documents relating to course provision and data on costs were gathered and analysed.

In the second phase of the study, questionnaires seeking views on evaluation were administered to GDPs attending Section 63 courses in the Autumn of 1996 in three local centres. The centres were selected on the basis of variation in size, locality and facilities. Questionnaires were sent to all GDPs attending a sample of nine courses running between October and December 1996. These nine courses were selected to reflect variety (small seminars, hands-on courses and large lecture courses), and provided a sample of 194 GDPs, a response rate of 57%. All the thirteen lecturers providing these courses were also sent questionnaires.

The results of Phase 2 were used to inform Phase 3 of the project, during which time a structured evaluation procedure was developed. This included the development of the evaluation instruments (questionnaires and pro forma) and the establishment of a formal mechanism for sharing evaluation data between tutors.

In Phase 4 the revised evaluation procedure was piloted on all the short courses running in the three study centres in the month of October 1997. The evaluation procedure was observed by a member of the research team on seven occasions. For all 21 courses, attendance and costs data were collected; participants completed an immediate post-course questionnaire; and lecturers completed a self-evaluation form. For all small group courses (ten or fewer participants) lecturers held a brief discussion with the group and completed an evaluation form based on this discussion. For tutor-selected courses (one in each centre) the course was observed by the tutor and an evaluation form completed. In addition a small number of courses were subject to a delayed impact-on-practice questionnaire approximately six weeks after the course.

During the pilot each of the evaluation forms included an extra set of questions 'about evaluation'. These questions were intended to gauge respondents' views on the usefulness of the form and to invite suggestions for improvement. Suggestions were then incorporated into the final procedures and instruments.

Results

Phase 1 revealed that some quantitative monitoring of short courses took place: attendance at courses was logged by the tutor and copied to the postgraduate office. Some courses were evaluated, but the prevalence and scope of evaluation was inconsistent.

Data collected in Phase 2 revealed that 85% of dentists surveyed had been asked to respond to an immediate post-course questionnaire (the most common tool used in evaluation) in the past. Tutors read through the responses to these questionnaires and provided some feedback to the course lecturers. However, the data were neither analysed in a structured manner nor shared with other local tutors. The course lecturers surveyed made considerable use of discussion with local tutors and courses participants, particularly as a means of informally evaluating small hands-on sessions. Approximately one third of the GDPs surveyed had had an evaluation discussion with the course lecturer. Tutors usually attended courses themselves and made judgements about them. Informal evaluations were based on the tutor's own criteria - whether people seemed satisfied, whether they kept coming, and so forth Again, these views were not shared between tutors. Finally, the data collected revealed that longer term impact on practice — the extent to which short courses lead to better patient treatment or alter practice — was not being evaluated.

These inconsistencies were reflected in the satisfaction levels of the GDPs. From the survey of dentists, although the majority thought the current evaluation procedures were adequate, a sizeable proportion (44%) thought them inadequate. The general view - across tutors, lecturers and GDPs - was that a more structured and rigorous evaluation would be useful.

The revised procedure, which includes assessments of cost-effectiveness, impact-on-practice and which is linked to a quality development cycle, was developed in Phase 3 and piloted in Phase 4. A total of 268 immediate post-course questionnaires were completed (a response rate of 82%); 20 lecturers' self-evaluation forms (a 95% response rate); 3 tutor evaluation forms; 4 small course discussion forms; and 42 delayed impact-on-practice questionnaires.

The results of Phase 4 indicated that course participants were positive in their response to evaluation: there was a significant majority in favour of all courses being evaluated; believing that the completion of the immediate post-course questionnaire was a useful exercise and one which would contribute to course improvement. Most thought it best to complete and hand in the post-course questionnaire on the day of the course (92%). Most lecturers shared this view (86%).

Lecturers were also positive about the principle of evaluation - 90% thought that all courses should be evaluated. Whilst 95% thought that completion of the self-evaluation form was a useful exercise, not all of these respondents believed that self evaluation by lecturers contributed to course improvement. Many lecturers indicated that they would value feedback on their sessions however. Little additional information was gained from the discussion with lecturers at the end of the courses.

The longer term impact-on-practice was also evaluated in the pilot. The response rate to the delayed impact-on-practice questionnaires was excellent from the two smaller courses (95% and 89%), but was lower for the larger lecture (36%). Only one respondent thought that the evaluation form was not appropriate. There was some disagreement on the optimum interval of time between actual attendance at a course and the assessment of the course's impact-on-practice. Taken as a whole the responses suggested an interval of about six weeks, although participants of smaller courses were in favour of a longer interval. The courses deemed most likely to impact on practice were those which offered updates on common clinical practice, especially if they are of a hands-on nature (for more detail see Bullock et al.9).

Discussion

Consultation with course participants, clinical tutors, lecturers and the regional postgraduate office in the West Midlands endorsed the need for a more structured framework for evaluation. The pilot exercise demonstrated that the evaluation instruments could be quickly and easily completed, that they were useful and could contribute to course improvement. Some modifications to the instruments and procedures were needed and these were incorporated into the evaluation framework recommended in the final report.10 Modifications included removing the small-course discussion element from the procedure as it was shown to provide insufficient additional information to warrant the effort.

The evaluation framework has been adopted as policy in the West Midlands. The framework has the capacity to be applied more widely and was outlined at the inaugural National Dental Tutors' Conference in Warrington in November 1998. There was widespread support for a system of evaluation, developed by the profession; if not nationally uniform, such a system should have a core framework. The West Midland's framework presents one model.

The new framework

In the West Midland's model, at all courses participants are asked to complete an immediate post-course questionnaire. To encourage a good response rate, these are administered by the course lecturer in a time-tabled slot at the end of the course: non-response makes evaluation data difficult to interpret. This questionnaire assesses the value, relevance and appropriateness of the course. In addition the lecturer(s) on all courses are requested to complete a brief self-evaluation form. This instrument allows the presenter to reflect on how well the course was received and to consider any future revisions. Tutors also complete a brief evaluation form for one or two courses per half year and assess how well the course was received by the participants and consider whether they would run it again and/or recommend it to others.

Course members attending a small number of specific courses are sent a delayed impact-on-practice questionnaire by the local tutors approximately 6 weeks after the course. The returns provide basic data on the extent to which attendance on short courses impacts on later practice, as assessed by the course participants themselves. As with all self-assessments, the validity of the response cannot be assumed but given time and financial constraints and by employing mechanisms which encourage honesty (for example, guaranteeing anonymity), useful data can be obtained from this approach. The postgraduate office is responsible for identifying those courses that are appropriate for the evaluation of impact-on-practice. 'High' cost per participant is usually one criterion, and this tends to identify small hands-on courses. For these courses a cost-effectiveness assessment is also made, comparing costs and learner outcomes (using responses on the immediate post-course and the delayed impact-on-practice questionnaires). Data from the immediate postcourse and the delayed impact-on-practice questionnaires are summarised by local tutors and disseminated to other tutors, the regional postgraduate office and lecturers. For all courses, the regional postgraduate office prepares an annual review of GDP attendance, collects costs data and calculates a course cost-per-participant. Guidelines have been drawn up to help manage the dissemination process.

From discussion at the National Dental Tutors' Conference it was evident that there is considerable use of immediate post-course questionnaires in other regions. Further, there is much overlap in terms of question areas and therefore scope to develop an agreed set of core immediate post-course questions. What is also evident, however, is the limited sharing of the evaluation information with other tutors in each deanery or between deaneries. Typically, evaluation forms are remitted to the postgraduate office but the information does not feed into a planning cycle, and cost-effectiveness and the assessment of impact-on-practice are neglected.

Cost-effectiveness

Provision needs to make best use of limited resources. The essence of cost-effectiveness is straight forward in that it relates costs to outcomes. However, there are a number of difficulties in its estimation in practice. Here the concept is discussed but briefly, identifying difficulties and its application within this framework. What is not considered here is how the cost-effectiveness of the evaluation process itself might be assessed.

Firstly, there are difficulties in assessing effectiveness. With regard to the Department of Health's definition of CPD,11 effective CPD should be relevant to individuals and organisations, meet its internal objectives and, ultimately, improve patient care through impact on practice. It is also not easy to identify costs and their functions. Costs are resources such as staff time (lecturers and administrators), learning materials, participants' and employers' time. Four types of cost are important: marginal costs (the extra costs of extra CPD activity); variable costs (how costs increase as CPD activity varies); fixed costs (costs irrespective of the amount of activity); and opportunity costs (alternative use of resources, including time).

In the evaluation model outlined here proxy indicators of effectiveness are drawn from the self-assessment questionnaires and related to data on costs (the costs of the lecturer(s), venue, equipment, administration, materials and overheads). No data on opportunity costs are used. Data drawn from the questionnaires are the participants' self assessments of the relevance of the course, their learning improvement and satisfaction. The resulting cost-effectiveness assessments are crude but they enable some judgement to be made of relative cost-effectiveness. If costs differ between courses with the similar outcomes, then the higher cost course is less cost-effective. Such rankings may be used to evaluate small hands-on courses, which are the most expensive, but may also be the most effective. Examining cost alone may also be beneficial in identifying economies of scale or possible areas for resource redistribution. Cost-effectiveness analysis is not however a substitute for professional judgement in the evaluation framework described here. There may be justifiable differences if, for example, some programme areas may be a national priority for GDPs; others are hands-on or have unavoidably low attendance; and if capacity constraints arise.

A Quality Development Cycle

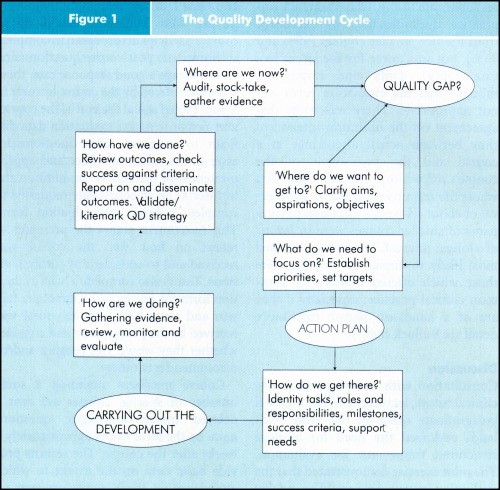

An important feature of the evaluation framework is its link into a quality development cycle. Not only does evaluation data need to be gathered, analysed and disseminated, but provision should also be reviewed in the light of the evaluation data and appropriate action planned. Action planning is an essential step in a quality development cycle. A quality development cycle enables both general response to local needs and the application of the evaluation information with regard to specific courses and lecturers.

Such a cycle involves six stages of activity.12 This is illustrated in Figure 1:

The Quality Development Cycle

The proposed evaluation framework recommends that each local centre should be under review once in 5 years. This will begin with an audit of continuing dental education using the twice yearly summaries prepared by tutors for their meetings (what courses are run, attendance, needs, costs, evaluation). The next step will be to clarify aims and aspirations for the next three years (for example, to target those GDPs who rarely attend courses) and then to prioritise these. An action plan designed to achieve these aims will be established (questioning target groups to ascertain reasons for non attendance and interests/needs etc.). During the implementation of this plan, progress will be monitored (the analysis of attendance data). This might lead to a modification of the action plan. The next review period would begin by looking back on the previous aims and assessing the extent to which they were achieved before setting aims for the next review period. Thus the framework goes beyond the gathering of data to actually using it to inform the provision of relevant, high quality courses. By assigning roles and responsibilities to all the groups involved in CPE for dental practitioners it supports the evaluation and dissemination of data, as well as helping to identifying opportunities for future planning of CPE.

The information gathered could also feed into a national body which could act to facilitate the modification of national planning of short course provision based on regional responses, and ensure co-ordination of educational activity. COPDEND (Conference of Postgraduate Dental Deans and Directors) in conjunction with the NCCPED (National Centre for Continuing Professional Education of Dentists) might perform such a role. The National Dental Tutors' Conference supported an enhanced role for COPDEND.

Conclusion

Short courses provide general and community dental practitioners with the opportunity to update their skills and knowledge to the ultimate benefit of patients. Currently, the shape of an individual's continuing professional education (CPE) is irregular: short courses are voluntary and typically chosen in an ad hoc fashion. However, if it becomes mandatory for dentists to attend courses they will need to be of a high quality, not least because course attendance has cost implications for their practices. Structures must be in place to ensure quality and, in part, this depends on providers of CPE following appropriate evaluation procedures. From the audit of existing evaluation practices in relation to short courses for GDPs in the West Midlands, and discussion from the National Dental Tutors Conference, it is clear that there was scope for a more structured approach to evaluation, both regionally and nationally.

This paper has described the framework developed in the West Midlands. The evaluation framework describes the roles and responsibilities of relevant parties, and the procedure followed - which courses are subject to which evaluation instruments. The evaluation procedure also includes an analysis of cost-effectiveness and impact-on-practice where appropriate. Both of these are new developments for the region, and do not appear to be applied in other areas either. Meaningful evaluation should include four key processes: gathering the data, analysing the data, disseminating the results and, finally, action planning. This fourth process links evaluation into a quality development cycle, which is central to the provision of a more needs-focused and structured programme of CPE.

References

-

Department of Health. Promoting Better Health. London: HMSO Department of Health, 1987, CM249.

-

Mouatt B, Veale B and Archer K . Continuing education in the GDS: an England survey. Br Dent J 1991; 170: 76–79.

-

Long A F, MacGregor A J and Mercer P E . Updating practices among Yorkshire General Dental Practitioners. Br Dent J 1991; 170: 73–75.

-

Walmsley A D and Frame J W . Dental practitioner attendances at postgraduate courses in a dental school. Br Dent J 1990; 169: 61–63.

-

Walmsley A D and Frame J W . Dental practitioner attendances at postgraduate courses in a dental school 1988-90. Dent Update 1992; 129–131.

-

Mercer P E, Long A F, Ralph J P and Bailey H . Audit activity and uptake of postgraduate dental education among General Dental Practitioners in Yorkshir. Br Dental J 1998; 184: 138–142.

-

General Dental Council. Reaccreditation and Recertification for the Dental Profession: A Consultation Paper. London: GDC, 1997.

-

General Dental Council. Statement on Continuing Education. London: GDC, 1993.

-

Bullock A D, Belfield C R, Butterfield S, Frame J W and Ribbins P M . Continuing education courses in dentistry: assessing impact on practic. Med Educ 1999; 33: 484–488.

-

Belfield C R, Bullock A D, Butterfield S, Frame J W and Ribbins P M . A Framework for the Evaluation of Short Courses in Dentistry: Final Report Birmingham: The University of Birmingham, 1998.

-

Department of Health. A First Class Service London: Department of Health, 1998.

-

Developed by Burridge, E and Ribbins, P. Promoting Improvement in schools. In Ribbins, P and Burridge, E. (eds.) Promoting Quality in Schools, London. 191–217. London: Cassell, 1993.

Source: https://www.nature.com/articles/4800300

0 Response to "Sample Survey for Continuing Education in Dentistry Pdf"

Post a Comment